Wireshark Lab: HTTP |

| This lab assignment is based on "Wireshark Lab:

HTTP", by J.F. Kurose, K.W. Ross, available

here. It has been prepared and revised by Farrokh Ghani Zadegan, Niklas Carlsson and Carl Magnus Bruhner. Last updated August 2024 (based on v8.0). |

Contents

- Overview of the Assignment

- The Basic HTTP GET/response interaction

- The HTTP CONDITIONAL GET/response interaction

- Retrieving Long Documents

- HTML Documents with Embedded Objects

- HTTP Authentication

- HTTP Persistent connection

- Demonstration and Report

Second, you will be asked to answer and/or discuss a number of questions. To save time, it is important that you carefully read the instructions such that you provide answers in the desired format(s). The appropriate HTTP traces can be found here (or locally).

We recommend installing Wireshark on your own computer and make your own traffic captures to analyze.

- You can run Wireshark by using the wireshark command. Note that you cannot collect traces on the lab computers, but must instead download, open, and analyze the traces provided by Kurose and Ross. (If you want to collect your own traces, you are encouraged to try this out on your own machine (for which you have administrative rights).

- Additional HTTP traces: If you want additional HTTP traces that you want to try to investigate (and reverse engineer) what is going on, you can also look at some of the other HTTP traces in the above zip file.

Before you start, please consider the following:

- The information that appears [inside brackets] in Wireshark is from Wireshark itself and NOT part of the protocols, and as such are not valid as a source for an answer.

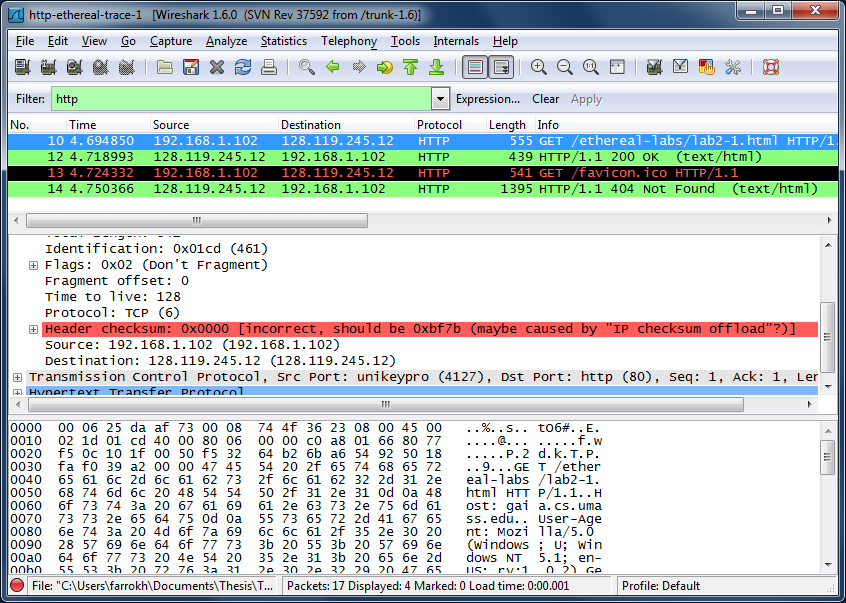

- Based on network settings of the platform on which you are running Wireshark, you may observe that all the outbound packets are marked by Wireshark as having checksum errors, see Figure 1. This, as suggested by Wireshark (see the packet details pane in Figure 1), might be due to checksum offloading, a setting which relieves CPU from generating checksum values for outbound packets and leaves this job to be done by the network adapter. Since Wireshark captures the packets before they reach the network adapter, the checksum value for all the captured packets is zero. If you find this color coding distracting or annoying, you can simply disable the checksum error coloring rule from the View->Coloring Rules... menu item.

|

| Figure 1: Wireshark indicating TCP checksum errors |

The Basic HTTP GET/response interaction

Let’s begin our exploration of HTTP by downloading a very simple HTML file - one that is very short, and contains no embedded objects. Do the following:

- Start up your web browser.

- Start up the Wireshark packet sniffer, as described in the Introductory lab (but don’t yet begin packet capture). Enter “http” (just the letters, not the quotation marks) in the display-filter-specification window, so that only captured HTTP messages will be displayed later in the packet-listing window. (We’re only interested in the HTTP protocol here, and don’t want to see the clutter of all captured packets).

- Wait a bit more than one minute (we’ll see why shortly), and then begin Wireshark packet capture.

- Enter the following to your browser http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/HTTP-wireshark-file1.html Your browser should display the very simple, one-line HTML file.

- Stop Wireshark packet capture.

|

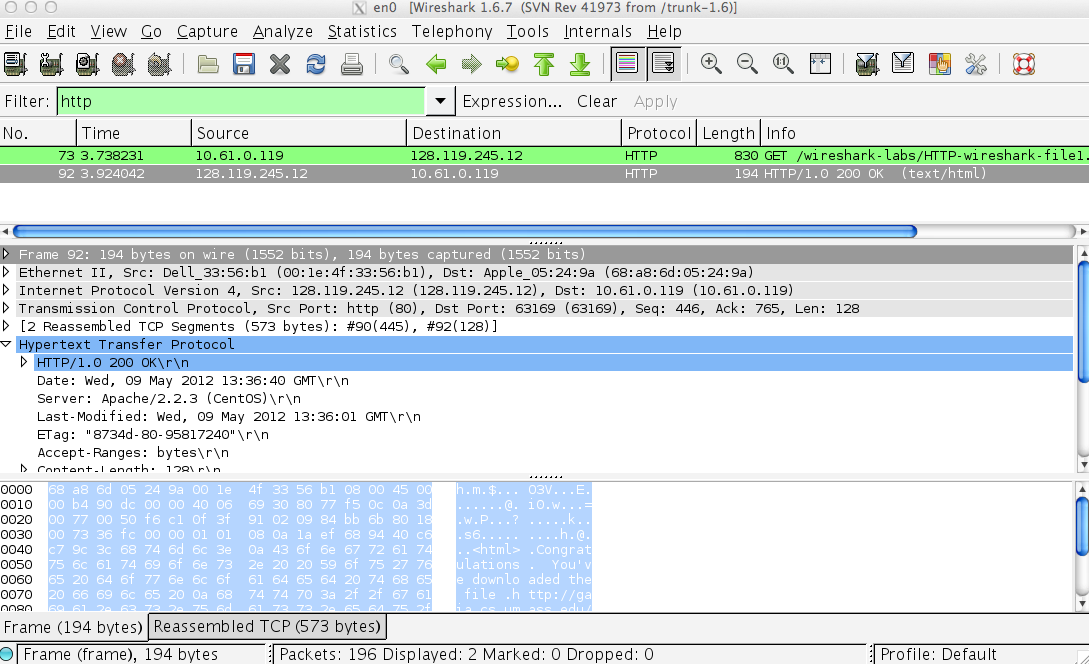

| Figure 2: Wireshark Display after http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/ HTTP-wireshark-file1.html has been retrieved by your browser |

| (Note: You should ignore any HTTP GET and response for favicon.ico. If you see a reference to this file, it is your browser automatically asking the server if it (the server) has a small icon file that should be displayed next to the displayed URL in your browser. We'll ignore references to this pesky file in this lab.). |

Instructions: By looking at the information in the HTTP GET and response messages, answer the following questions. When answering the following questions, you should print out the GET and response messages (see the introductory Wireshark lab for an explanation of how to do this) and indicate where in the message you’ve found the information that answers the following questions. When you hand in your assignment, annotate the output so that it’s clear where in the output you’re getting the information for your answer. To include the packet data in your own report, you may either attach screenshots or export the selected packet data as a text file. To do so, use the File->Export->File... window, select file type as Plain text, and choose "Selected packets only". (Note that the export procedure might differ based on the platform on which you are running Wireshark; e.g., macOS, Windows, etc.) Indicate where in the message you’ve found the information that answers the following questions. As for all questions in this course it is important that you clearly indicate what your answer is, how you obtained the answer, and (if applicable) discuss implications/insights regarding your answers. For example, in the questions below, can you elaborate on why you may have observed what you observed?

- Is your browser running HTTP version 1.0 or 1.1? What version of HTTP is the server running?

- What languages (if any) does your browser indicate that it can accept to the server?

- What is the IP address of your computer? Of the gaia.cs.umass.edu server?

- What is the status code returned from the server to your browser?

- When was the HTML file that you are retrieving last modified at the server?

- How many bytes of content are being returned to your browser?

- In the captured session, what other information (if any) does the browser provide the server with regarding the user/browser?

In your answer to question 5 above, you might have been surprised to find that the document you just retrieved was last modified within a minute before you downloaded the document. That’s because (for this particular file), the gaia.cs.umass.edu server is setting the file’s last-modified time to be the current time, and is doing so once per minute. Thus, if you wait a minute between accesses, the file will appear to have been recently modified, and hence your browser will download a “new” copy of the document.

Task A: For questions 1-7, first write a brief but precise answer for each of the above questions, then write a (combined) paragraph explaining and discussing your observations from the above practice questions. Note that your answer may benefit from explaining and/or referring to some of your observations explicitly.

The HTTP CONDITIONAL GET/response interaction

Recall from Section 2.2.5 of the text, that most web browsers perform object caching and thus perform a conditional GET when retrieving an HTTP object. Before performing the steps below, make sure your browser’s cache is empty. (To do this under Firefox, select Tools->Clear Recent History, for Internet Explorer, select Tools->Internet Options->Delete File, for Chrome, click More->More tools>Clear browsing data, for Safari, go to Safari->Preferences and activate Show Develop menu in menu bar under the Advanced tab, and then close and select Develop->Empty Caches. These actions will remove cached files from your browser’s cache.) Now do the following:

- Start up your web browser, and make sure your browser’s cache is cleared, as discussed above.

- Start up the Wireshark packet sniffer

- Enter the following URL into your browser http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/HTTP-wireshark-file2.html Your browser should display a very simple five-line HTML file.

- Quickly enter the same URL into your browser again (or simply select the refresh button on your browser)

- Stop Wireshark packet capture, and enter “http” in the display-filter-specification window, so that only captured HTTP messages will be displayed later in the packet-listing window.

- (Note: If you are unable to run Wireshark on a live network connection, you can use the http-ethereal-trace-2 packet trace to answer the questions below; see here. This trace file was gathered while performing the steps above on one of the author’s computers.)

Answer the following questions:

- Inspect the contents of the first HTTP GET request from your browser to the server. Do you see an “IF-MODIFIED-SINCE” line in the HTTP GET?

- Inspect the contents of the server response. Did the server explicitly return the contents of the file? How can you tell?

- Now inspect the contents of the second HTTP GET request from your browser to the server. Do you see an “IF-MODIFIED-SINCE:” line in the HTTP GET? If so, what information follows the “IF-MODIFIED-SINCE:” header?

- What is the HTTP status code and phrase returned from the server in response to this second HTTP GET? Did the server explicitly return the contents of the file? Explain.

In our examples thus far, the documents retrieved have been simple and short HTML files. Let’s next see what happens when we download a long HTML file. Do the following:

- Start up your web browser, and make sure your browser’s cache is cleared, as discussed above.

- Start up the Wireshark packet sniffer

- Enter the following URL into your browser http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/HTTP-wireshark-file3.html Your browser should display the rather lengthy US Bill of Rights.

- Stop Wireshark packet capture, and enter “http” in the display-filter-specification window, so that only captured HTTP messages will be displayed.

- (Note: If you are unable to run Wireshark on a live network connection, you can use the http-ethereal-trace-3 packet trace to answer the questions below; here. This trace file was gathered while performing the steps above on one of the author’s computers.)

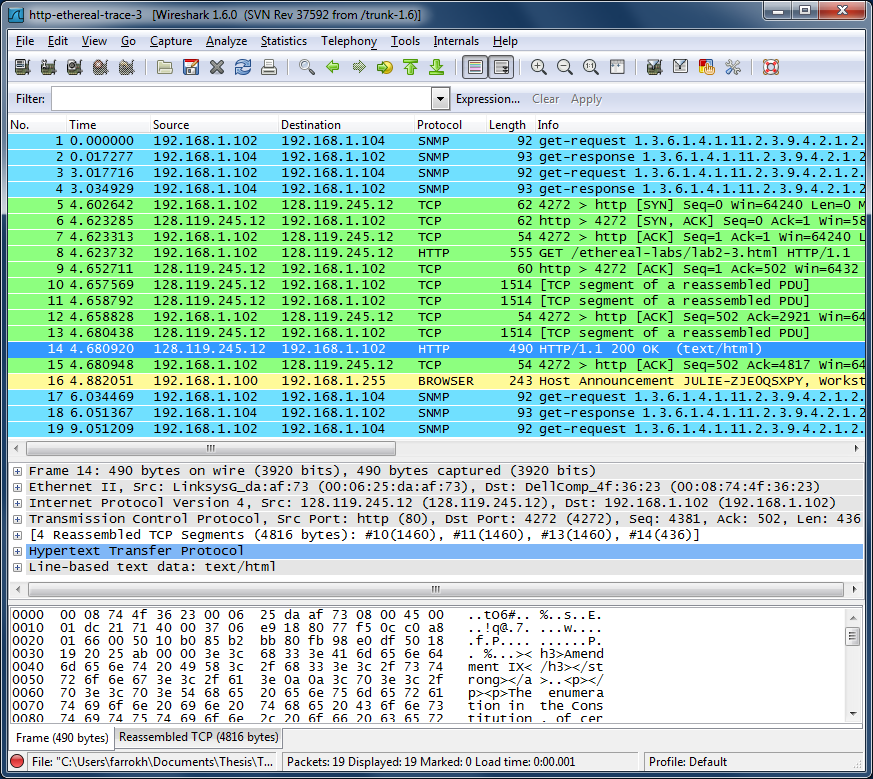

In the packet-listing window, you should see your HTTP GET message, followed by a multiple-packet response to your HTTP GET request. This multiple-packet response deserves a bit of explanation. Recall from Section 2.2 (see Figure 2.9 in the text) that the HTTP response message consists of a status line, followed by header lines, followed by a blank line, followed by the entity body. In the case of our HTTP GET, the entity body in the response is the entire requested HTML file. In our case here, the HTML file is rather long, and at 4500 bytes is too large to fit in one TCP packet. The single HTTP response message is thus broken into several pieces by TCP, with each piece being contained within a separate TCP segment (see Figure 1.24 in the text). In recent versions of Wireshark, Wireshark indicates each TCP segment as a separate packet, and the fact that the single HTTP response was fragmented across multiple TCP packets is indicated by the “TCP segment of a reassembled PDU” in the Info column of the Wireshark display. Earlier versions of Wireshark used the “Continuation” phrase to indicated that the entire content of an HTTP message was broken across multiple TCP segments.. We stress here that there is no “Continuation” message in HTTP! In this regard, Figure 3 shows a screenshot of Wireshark displaying http-ethereal-trace-3 packet trace. In the listing of the captured packets, packet No. 8 shows the HTTP GET request and packet No. 14 shows the corresponding HTTP response. It can be seen that the packets No. 10, 11 and 13 are labeled with “TCP segment of a reassembled PDU”. By clicking on the HTTP response, i.e. packet No. 14, the packet details pane shows [4 Reassembled TCP Segments (4816 bytes): #10(1460), #11(1460), #13(1460), #14(436)] (see Figure 3). Additionally, the packet bytes pane shows a new tab titled Reassembled TCP which shows the entire received HTTP response.

|

| Figure 3: Wireshark display showing http-ethereal-trace-3 packet trace |

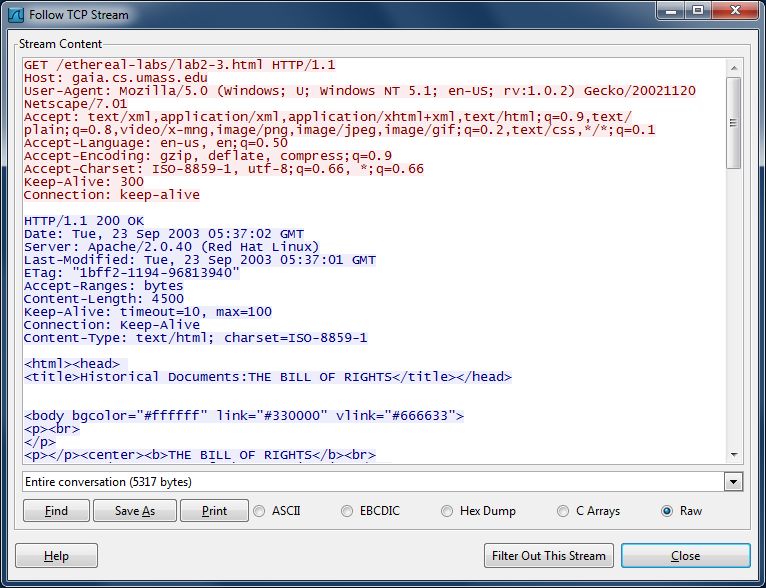

A more convenient way to view the entire data (i.e. all HTTP requests and responses transported in a TCP stream) is using a Wireshark feature called "Follow TCP Streams". By right-clicking on any of the TCP packets associated with a given TCP stream and selecting the "Follow->TCP Stream" menu item, a new window pops up that contains the data exchanged in the selected stream. Figure 4, shows the "Follow TCP Stream" window for the GET /ethereal-labs/lab2-3.html HTTP/1.1 request and its complete associated response. In this window, the non-printable characters are replaced by dots. However, the choice of Raw or ASCII in this window, affects the way you can save the entire stream. That is, if Raw is selected, the stream is saved as a binary file preserving the non-printable characters, whereas in the case of ASCII, the stream is saved as a text file in which the non-printable characters are replaced by dots. Please note how Wireshark has changed (and applied) the display filter to show only the packets in the selected stream.

|

| Figure 4: The "Follow TCP Stream" window |

Answer the following questions:

- How many HTTP GET request messages did your browser send? Which packet number in the trace contains the GET message for the Bill or Rights?

- Which packet number in the trace contains the status code and phrase associated with the response to the HTTP GET request? What is the status code and phrase in the response?

- How many data-containing TCP segments were needed to carry the single HTTP response and the text of the Bill of Rights?

- Is there any HTTP header information in any of the transmitted data packets associated with TCP segmentation? For this question you may want to think about at what layer each protocol operates, and how the protocols at the different layers interoperate.

HTML Documents with Embedded Objects

Now that we’ve seen how Wireshark displays the captured packet traffic for large HTML files, we can look at what happens when your browser downloads a file with embedded objects, i.e., a file that includes other objects (in the example below, image files) that are stored on another server(s). Do the following:

- Start up your web browser, and make sure your browser’s cache is cleared, as discussed above.

- Start up the Wireshark packet sniffer

- Enter the following URL into your browser http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/HTTP-wireshark-file4.html Your browser should display a short HTML file with two images. These two images are referenced in the base HTML file. That is, the images themselves are not contained in the HTML; instead the URLs for the images are contained in the downloaded HTML file. As discussed in the textbook, your browser will have to retrieve these logos from the indicated web sites. Our publisher’s logo is retrieved from the gaia.cs.umass.edu web site. The image of the cover for the 5th edition is stored at the caite.cs.umass.edu server. (These are two different web servers inside cs.umass.edu).

- Stop Wireshark packet capture, and enter “http” in the display-filter-specification window, so that only captured HTTP messages will be displayed.

- (Note: If you are unable to run Wireshark on a live network connection, you can use the http-ethereal-trace-4 packet trace to answer the questions below; see here. This trace file was gathered while performing the steps above on one of the author’s computers.)

Answer the following questions:

- How many HTTP GET request messages were sent by your browser? To which Internet addresses were these GET requests sent?

- Can you tell whether your browser downloaded the two images serially, or whether they were downloaded from the two web sites in parallel? Explain.

Finally, let’s try visiting a web site that is password-protected and examine the sequence of HTTP message exchanged for such a site. The URL http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/protected_pages/HTTP-wireshark-file5.html is password protected. The username is “wireshark-students” (without the quotes), and the password is “network” (again, without the quotes). So let’s access this “secure” password-protected site. Do the following:

- Make sure your browser’s cache is cleared, as discussed above, and close down your browser. Then, start up your browser

- Start up the Wireshark packet sniffer

- Enter the following URL into your browser http://gaia.cs.umass.edu/wireshark-labs/protected_pages/HTTP-wireshark-file5.html Type the requested user name and password into the pop up box.

- Stop Wireshark packet capture, and enter “http” in the display-filter-specification window, so that only captured HTTP messages will be displayed later in the packet-listing window.

- (Note: If you are unable to run Wireshark on a live network connection, you can use the http-ethereal-trace-5 packet trace to answer the questions below; see here. This trace file was gathered while performing the steps above on one of the author’s computers.)

Now let’s examine the Wireshark output. You might want to first read up on HTTP authentication by reviewing the easy-to-read material on “HTTP Access Authentication Framework” at http://frontier.userland.com/stories/storyReader$2159

Answer the following questions:

- What is the server’s response (status code and phrase) in response to the initial HTTP GET message from your browser?

- When your browser sends the HTTP GET message for the second time, what new field is included in the HTTP GET message?

The username (wireshark-students) and password (network) that you entered are encoded in the string of characters (d2lyZXNoYXJrLXN0dWRlbnRzOm5ldHdvcms=) following the “Authorization: Basic” header in the client’s HTTP GET message. While it may appear that your username and password are encrypted, they are simply encoded in a format known as Base64 format. The username and password are not encrypted! To see this, go to http://www.base64decode.org/ (or any other Base64 decoder of your choice) and enter the base64-encoded string d2lyZXNoYXJrLXN0dWRlbnRz into the "Decode from base64" text box and press "Go". Voilà! You have translated from Base64 encoding to ASCII encoding, and thus should see your username! To view the password, enter the remainder of the string Om5ldHdvcms= and press decode. Since anyone can download a tool like Wireshark and sniff packets (not just their own) passing by their network adaptor, and anyone can translate from Base64 to ASCII (you just did it!), it should be clear to you that simple passwords on WWW sites are not secure unless additional measures are taken.

Fear not! As we will see in Chapter 8, there are ways to make WWW access more secure. However, we’ll clearly need something that goes beyond the basic HTTP authentication framework!

- What does the "Connection: close" and "Connection: keep-alive" header field imply in HTTP protocol? When should one be used over the other?

For this assignment you will need to write a report that carefully answers questions 1-19 (+ 20), as well as provides one paragraph discussing each of the set of questions: 1-7 (task A), 8-11 (task B), 12-15 (task C), 16-17 (task D), 18-19 (task E) and 20 (no paragraph needed). Note that each group of questions has a theme and you are expected to convince the reader of your report (including yourself if you were to read the document weeks/months later) that you understand these aspects of HTTP.

Please structure your report such that your answers are clearly indicated for each question (and section of the assignment). It is not the TA's task to search for the answers. Both the questions themselves and the corresponding answers should be clearly stated (and indicated) in your report. Structure your report accordingly. Furthermore, your answers should be explained and supported using additional evidence, when applicable. During the demonstration the TA may ask similar questions to assess your understanding of the lab. You are expected to clearly explain and motivate your answers. As the assignments are done in groups of two, both members of the group will be asked to answer questions.

It is important that you demonstrate the assignment (and discuss your report) with the TA before handing in the report. Also, in addition to having a draft of the report ready, please make sure to open Wireshark and have the trace files ready before calling the TA for the demonstration.

Additional instructions and information about the reports can be found here. Please take this chance to read the guidelines carefully.